Montreal

| Montreal | |||||

From top to bottom and left to right: downtown Montreal, Old Montreal, Notre-Dame Basilica, Old Port of Montreal, Saint-Joseph Oratory, Olympic Stadium. | |||||

Arms of Montreal. | Flag of Montreal. | ||||

| Administration | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | |||||

| Province | |||||

| Region | Montreal | ||||

| Regional Subdivisions | Montreal | ||||

| Municipal Statute | Metropole | ||||

| Arrondissements | 19 arrondissements | ||||

| Mayor Mandate | Valérie Plante 2017-2021 | ||||

| Founder Foundation Date | Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve | ||||

| Constitution | |||||

| Demographics | |||||

| Gentile | Montrealers | ||||

| Population | 1,704,694 hab. () | ||||

| Density | 4,662 inches/km2 | ||||

| Urban area population | 4,098,927 hab. (2016) | ||||

| Geography | |||||

| Coordinates | 45° 30′ 32′ north, 73° 33′ 42′ west | ||||

| Area | 36,565 ha = 365.65 km2 | ||||

| Miscellaneous | |||||

| Language(s) | French | ||||

| Time zone | Eastern Time | ||||

| Indicative | 514 and 438 | ||||

| Geographic code | 66023 | ||||

| Currency | Concordia Salus ("Salvation through Concord") | ||||

| Location | |||||

Location of Montreal in its metropolitan area | |||||

| Geolocation on the map: Montreal Metropolitan Area

Geolocation on the map: Quebec

Geolocation on the map: Canada

Geolocation on the map: Canada

| |||||

| Links | |||||

| Website | montreal.ca | ||||

Montreal/ˈ m ɔ̃. ˌ ʁ e. a l , in long form the City of Montreal, is the largest city in Quebec and the second most populated city in Canada, after Toronto and before Vancouver. It is located mainly on the river island of Montreal, on the St. Lawrence River (between Quebec and Lake Ontario) in southern Quebec, of which it is the metropolis.

At the time of the 2016 census of Canada, the city had 1,704,694 inhabitants. Its urban area, called the Montreal Metropolitan Area, encompasses more than 4 million inhabitants, or about half of the population of Quebec. Montreal is thus the 19th most populated city in North America and the 122th most populated city in the world. The most populous French-speaking city in America, Montreal is considered to have the second largest French-speaking population in the world after Paris. According to the 2016 census, 53.4% of the population of Montreal was French-speaking, 15.1% was English-speaking, and 36.8% was third-language, making it one of the most cosmopolitan cities in the world.

Montreal is the 3th largest financial center in North America and the 12th in the world. The economic heart of Quebec, Montreal is also Canada’s second-largest financial center and has a highly diversified economy through trade, education, information technology and the aerospace, pharmaceutical, tourism and film industries. The city is the 3th largest in the global video game industry. Classified as a World City in 2012, Montreal is the second largest city in North America, home to the International Civil Aviation Organization, and home to more than 65 international governmental and non-governmental organizations, making it the 3th largest city in North America in terms of the number of head offices of international organizations, behind New York and Washington. In addition, the city is the first city in North America for the number of international congresses. In 2017, Montréal was named the "best student city" in the world and is considered the "University Metropolis of Canada, with six universities and 450 research centers".

Montreal hosts several major international events, including the 1967 World Exhibition and the 1976 Summer Olympics. Hosted by Canada's Formula 1 Grand Prix, it hosts many festivals annually, such as the Montreal International Jazz Festival, the FrancoFolies and Just for Laughs. The Montreal Canadiens Hockey Club opened in 1909.

Toponymy

Montreal is pronounced [ɔ̃ e a l] in standard french, [m ɒ̃ e a l ] in french québécois and [ˌ m ʌ n t r i ɒ ˈ l ] in canadian english. The Kanien'kehá:ka (Mohawks) refer to Montreal as Tio'tia:ke which means "where the currents meet" or "the island between the two rapids".

It was the French explorer Jacques Cartier, on his second trip to America in 1535, who named the mountain that overlooks the city. In his travel account, he says: "And among these countryside lies and sits the town of Hochelaga near a mountain in the vicinity of the plowed and very fertile and on which you can see far away. We named this mountain Mount Royal. "The choice of this name could be attributed to Jacques Cartier who accompanied Jacques on the day of landing on this island, Claude de Pontbriand, son of the lord of Montreal (province of Aquitaine, Kingdom of France). This is the opinion of historians Henry Percival Biggar and AEgidius Fauteux. From the seigneury of Montreal in Aquitaine, the castle remains.

The shape of the toponym Montréal (instead of a expected *Montroyal) was attested in 1575 by François de Belleforest, a gentleman from the south of France. Indeed, the toponymic type Montréal, common in the south of France, is mainly characteristic of the language of oc, spoken in most of this region, while it is rare in the area of oyl (isolated examples). The term mont in French (and in the language of oc) comes from the Gallo-roman MONTE (himself from the accusative montem, from the Latin less "mountain"), he also had the meaning of "height, elevation, hill" in former French. Real generally represents the form of a francised oc (modern Occitan reial, reial, "royal") corresponding to the former central French royal that is attested in this form from the Middle Ages and from the oldest reial/roial, whose primitive regiel form is attested in the Sequence of St. Eulalia around the year 88. 0, but whose final it was redone in al in accordance with the latin etymology regalis. This alternative form real can be found in some texts in ancient French, as in Erec and Enide de Chrétien de Troyes, dating back to the 12th century. Occitan generally retains the -al form of Latin, sometimes mutated into -au (cf.nadal / nadau correspondent of christmas).

Although the first French establishment on the island of Montreal was named Ville-Marie, the name Montréal became the de facto name of the city as of the 17th century; several cards bear witness to this. This designation became official on , the date of incorporation of the "City of Montreal".

Geography

Situation and territory

Montreal is 165 km east of Ottawa, 232 km southwest of Quebec City and 3686 km northeast of Vancouver. The city is located at 45° 31′ north latitude and 73° 39′ west longitude in southern Quebec, Canada, close to the Province of Ontario and the State of New York in the United States. The city occupies 74.5% of the 482.8 km2 of Montreal Island, the largest river island in the Hochelaga Archipelago, at the confluence of the St. Lawrence River and the Ottawa River. The Island of Montreal is bounded on its south shore, west to east, by Lake Saint-Louis, the Lachine rapids, the Prairie Basin and the St. Lawrence River itself. On its north shore it is bathed by the Lac des Deux Montagnes and then by the Rivière des Prairies. The city also includes Bizard Island, Sisters Island, Sainte-Hélène Island and Notre-Dame Island.

Montreal is part of the St. Lawrence Lowlands ecoregion, a vast valley between the Appalaches and Laurentides Mountains, stretching along the St. Lawrence River. The highest point on the island, Mount Royal, one of the Montérégiennes hills, spans the city center at 234 meters. The municipal zoning ensures that no construction exceeds this height for aesthetic reasons[ref. desired]. The historic center of the city, also known as Old Montreal, is located on the banks of the St. Lawrence River, a few kilometers downstream of the Lachine rapids. The hypercenter, with its skyscrapers, is located nearby, on a terrace between the river and the southern slope of Mount Royal.

The territory of the Municipality of Montreal extends over 365.65 km2; It is home to the cities of Montreal East, Mont-Royal, Hampstead, Côte-Saint-Luc, Montréal West and Westmount, and shares land borders in the west of the island with Beaconsfield, Baie-d'Urfé, Dorval, Dollard-Des Ormeaux, Kirkland, Pointe-Claire, Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue and Senneville.

Quarters and arrondissements

Founded in the area that is now Old Montreal, in the borough Ville-Marie, Montréal has seen its division and the boundaries of its territory change significantly since its establishment. The area of the city has been increased by the annexation of many municipalities, whose names are now found in the names of several neighborhoods and borhoods.

The 1st municipality to be merged in Montreal was Hochelaga in 1883, followed by Saint-Jean-Baptiste in 1886, Saint-Gabriel in 1887 and Côte-Saint-Louis in 1893. The year 1905 saw the integration of Villeray, Saint-Henri and Sainte-Cunégonde, today the district of La Petite-Bourgogne. In 1908, Notre-Dame-des-Neiges was added, then Saint-Louis-du-Mile-End and De Lorimier a year later.

In 1910, no less than 10 municipalities were merged in Montreal: Tétreaultville, Longue-Pointe, Beaurivage-de-la-Longue-Pointe, Côte-Saint-Paul, Ville-Émard, Rosemont, Bordeaux, Ahuntsic, Côte-des-Neiges and Notre-Dame-de-Grâce, the last two being the arrondissement of the same name. Six years later, the city expanded once again, encompassing Sault-au-Recollet and Cartierville, and then Maisonneuve in 1918.

The municipal territory remained stable for more than four decades, until the annexation of Rivière-des-Prairies in 1963, Saraguay in 1964 and Saint-Michel in 1968. Thirteen and fourteen years later came the tour of Saint-Jean-de-Dieu and Pointe-aux-Trembles.

At the beginning of the 21st century, a reorganization of the municipalities was implemented throughout Quebec. After a process of massive mergers followed by several demergers, Montréal acquired its current limits after integrating Anjou, Lachine, LaSalle, Montréal-Nord, Outremont, Saint-Laurent, Saint-Léonard, Verdun, Pierrefonds, Roxboro, Saint-Raphaël-de-l'Île-Bizard and Sainte-Geneviève. The first eight entities become as many boroughs, while the last four are twinned to form only two: Pierrefonds-Roxboro and L'Île-Bizard-Sainte-Geneviève, the latter being the least populated district of the city.

Boundary municipalities

| Two Mountains, Sainte-Marthe-sur-le-Lac, Pointe-Calumet, Oka, Lac des Deux Montagnes | Laval, Terrebonne, Prairie River | Repentigny, Prairie River, Varennes, St. Lawrence River, Montreal East | ||

| Lac des Deux Montagnes, Senneville, Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue | N | St. Lawrence River, Boucherville, Longueuil, Saint-Lambert, Brossard | ||

| O Montreal E | ||||

| S | ||||

| Kirkland, Dollard-Des Ormeaux, Dorval, Lake Saint-Louis | Lac Saint-Louis, Saint-Laurent River, Kahnawake, Sainte-Catherine | St. Lawrence River, La Prairie | ||

| Enclave: Mont-Royal, Westmount, Hampstead, Côte-Saint-Luc, Montreal West | ||||

Climate

The Montreal area has a humid continental climate with a high thermal amplitude. From 1971 to 2000, the average annual temperature was 6.2 °C. The warmest month is July, with an average temperature of 20.9 °C, and the coldest is January with an average of -10.2 °C. There is an average of 8 days above 30 °C and 17 days below -20°C every year. The lowest temperature ever recorded was -37.8 °C on ; the highest temperature was 37.6 °C on . The highest humidex index was 46.8 on and the lowest wind chill was -49.1 on . According to a study published on by the Quebec Ministry of Sustainable Development, the Environment and Parks, the western part of southern Quebec has warmed from 1 to 1.25 °C from 1960 to 2003.

According to the Köppen classification: the average temperature of the coldest month is less than 0 °C (January with -9.7°C) and that of the hottest month is more than 10 °C (July with 21.2°C), which corresponds to a continental climate. Since the rainfall is stable, it is therefore a cold continental climate without a dry season. The summer is temperate, because the average temperature of the hottest month is less than 22 °C (July with 21.2°C) and the average temperatures of the hottest 4 months are higher than 10 °C (June to September with 18.6°C, 21.2 °C, 20.1°C respectively and 15.5°C).

The climate of Montreal is classified as Dfb in the Köppen classification, a humid continental climate with temperate summer.

In the period 1971 to 2000, Montreal received approximately 2,979 mm of precipitation per year, 764 mm as rain and 2,180 mm as snow. The median date of the first snow is 1to 15 December and the melting of the continuous snow cover is 1st to 15 April; a total of about 4 months snowy. The rainest day was , with 94 mm recorded in one day. The largest snowfall ever recorded in a single day took place on with a precipitation of 45 cm, while over a period of 24 hours the record was set from March 4 to 5, 1971, with a precipitation of 47 cm during the now famous "Storm of the Century". On December 26 and 27, 1969, Québec's metropolis saw its strongest storm with more than 70 cm in 48 hours. The largest snow cover was measured on with 102 cm.

| Month | jan. | Feb. | March | April | May | June | Jul | August | sep. | oct. | Nov | Dec. | year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average minimum temperature (°C) | -17 | -14.2 | -9.5 | 1.2 | 7.9 | 13.2 | 16.1 | 14.8 | 10.3 | 3.9 | -1.7 | -13.3 | 2 |

| Average Temperature (°C) | -9.7 | -7.7 | -2 | 6.4 | 13.4 | 18.6 | 21.2 | 20.1 | 15.5 | 8.5 | 2.1 | -5.4 | 6.8 |

| Average Maximum Temperature (°C) | -5.3 | -3.2 | 2.5 | 11.6 | 18.9 | 23.9 | 26.3 | 25.3 | 20.6 | 13 | 5.9 | -1.4 | 11.5 |

| Cold record (°C) record date | -37.8 1957 | -37 1934 | -29.4 1950 | -15 1954 | -4.4 1947 | 0 1995 | 6.1 1982 | 3.3 1957 | -2.2 1951 | -7.2 1972 | -19.4 1949 | -32.4 1980 | -37.8 1957 |

| Heat record (°C) record date | 13.9 1950 | 15 1981 | 25.6 1945 | 30 1990 | 34.7 2010 | 35 1964 | 35.6 1953 | 37.6 1975 | 33.5 1999 | 28.3 1968 | 21.7 1948 | 18 2001 | 37.6 1975 |

| Sunlight (h) | 101.2 | 127.8 | 164.3 | 178.3 | 228.9 | 240.3 | 271.5 | 246.3 | 182.2 | 143.5 | 83.6 | 83.6 | 2,051.3 |

| Precipitation (mm) | 77.2 | 62.7 | 69.1 | 82.2 | 81.2 | 87 | 89.3 | 94.1 | 83.1 | 91.3 | 96.4 | 86.8 | 1,000.3 |

| Climate Diagram | |||||||||||

| J | F | M | A | M | J | J | A | S | O | N | D |

-5.3 -17 77.2 | -3.2 -14.2 62.7 | 2.5 -9.5 69.1 | 11.6 1.2 82.2 | 18.9 7.9 81.2 | 23.9 13.2 87 | 26.3 16.1 89.3 | 25.3 14.8 94.1 | 20.6 10.3 83.1 | 13 3.9 91.3 | 5.9 -1.7 96.4 | -1.4 -13.3 86.8 |

| Average: ・ Time. max and mini°C・ Precipitation mm | |||||||||||

Environment

Fauna and flora

Just like the climate, the fauna and flora of the island of Montreal are part of the mixed forest ecosystem. The natural environment of the island includes several hardwood species such as sugar maple, beech, lime tree, yellow birch, gray walnut, white oak and conifers, such as Canada Hemlock, western cedar, white pine and red pine. The most common animal species are the raccoon, the striped skull, the gray squirrel and its melanchic black-jay and brown-black varieties, the common marmot, the white-tailed rabbit, the white-tailed deer, the gully of America, the blue jay, the large peak and the Baltimore oriole. Coyote is an increasingly common species in Montreal.

Montreal also boasts a great deal of commensurate wildlife. In addition to cats, dogs and other domestic animals, pigeons, gulls and rats live in urban areas.

Soil pollution

Montreal suffers the environmental consequences of its high population density, extensive urbanization, high motorization and industrial activity.

The industrial heart of Canada for nearly a century, the city currently has nearly 1,500 contaminated land on its territory. Examples of major land rehabilitation include Pointe-Saint-Charles Business Park, Frédéric-Back Park, Maisonneuve Park and Félix-Leclerc Park, former landfills.

Air pollution

In 2011, according to the World Health Organization, Montreal had one of the worst air qualities in Canada (after Sarnia in Ontario). However, for several years the air quality has improved on the island. Indeed, the m/g/m3 averages of annual concentrations of fine particles measured in Montreal increased from 11.4 µg g/m3 in 2009 to 7.0 µg g/m3 in 2016, while the World Health Organization standard is 10 g/m3.

Air quality in Montreal is monitored by the Air Quality Monitoring Network (AQIS), which has 14 stations on the Island of Montreal. In 2010, the body observed 65 days of bad air, including 24 days of smog.

Health Canada estimates that there are 1,540 premature deaths due to air pollution in Montreal each year. Automotive pollution is said to be responsible for more than 6,000 cases of childhood bronchitis per year[insufficient source]. Residents living along highways experience hospitalization rates 20% higher than the rest of the population.

Water pollution

Water quality in Montreal is monitored by the Aquatic Environment Tracking Network (AMTN), which analyzes streams, streams, inland lakes and storm sewers using 116 stations. The Prairie River, in the north of the island, has the highest water pollution; in 2010, half of the sites had too high bacteriological levels for swimming.

The availability of water around Montreal makes it very inexpensive to clean and clean up, less than 40¢ per cubic meter. In addition, the municipality does not charge its water by volume of consumption but by place through the property tax. In doing so, Montrealers are among the world's largest water users (1,104 liters/person/day). More than the low cost of water, this excess is mainly due to the large losses (35%) of dilapidated basement aqueducts. So one-quarter of the wastewater is actually drinking water that leaks directly into the sewers.

Sound pollution

The adjacent boroughs, located below the Montréal-Trudeau Airport air corridor, including Ahuntsic-Cartierville and Saint-Laurent, are particularly affected by noise pollution. Residents regularly denounce the failure to comply with the air curfew between 11 pm and 7 am[insufficient source]. Moreover, noise regulations can be quite different depending on the rounding.

Transport

While the City of Montreal has the lowest motorization rate in Canadian and U.S. cities, the automobile remains the dominant mode of transportation in the metropolitan area. In 2006, 70 per cent of working people in the metropolitan area went to work by car as drivers or passengers; this proportion falls to 53.2% among the city's residents, a number significantly lower than the quebec figure of about 78%.

Road and motorway network

Montreal is built on an archipelago of river islands that is not directly accessible from the rest of the continent. Like most major cities, it faces the problem of car congestion, which is only aggravated by its island situation. It takes an average of 31 minutes for a motorist from the Montreal area to get to work; one quarter of the drivers took more than 45 minutes. Because of its high urbanization, Montreal also has rush hours on Saturdays and Sundays.

Montreal is the nerve center of a 1,770-kilometer network of highways built mainly between the late 1950s and the mid-1970s in its periphery. 17 road bridges and a tunnel allow you to cross the rivers that surround the city. These include the Samuel-De Champlain Bridge, Canada's busiest bridge.

The island of Montreal has many fast roads, the main one being Highway 40, the only one to cross it from west to east. A segment of the Trans-Canada Highway, it is the busiest part of the metropolitan area, and its partially elevated metropolitan area has been the most congested part of it since its creation. Running perpendicular to the A-40, Highway 15, which stretches from the Laurentians to the American border, passes through a trench in the center of the island called the Décarie Highway, named after the boulevard it runs along.

Public transport

Public transportation on the Island of Montreal is one of the most efficient, fast and punctual in North America; the Société de transport de Montréal (STM), which administers it, was named, in 2010, the best transportation company in North America by the American Public Transportation Association. In Montreal, 35 per cent of the workforce goes to work by public transit; this proportion is 49% for newcomers. In total, the STM recorded 466 million trips in terms of conventional traffic and 374.9 million in terms of electronic traffic in 2019. Shopping has risen by 2.6% since 2018.

The Montreal subway is the backbone of the metropolitan transit system with approximately 1.2 million passengers a day. The metro station has 68 stations spread over 43 mi of lines. Designed on the Parisian metro model, the Montréal network has the particularity of being completely underground and its trains have a tire rolling system. Each resort has its own unique architecture and public art is found in most of them.

On the surface, the trams have been replaced since 1959 by 225 bus lines and 8,500 stops, served by a total of 1,869 buses and 93 adapted minibuses. The busiest bus line is 139 Pie-IX with an average of 32,313 trips per week. There are less than one million passengers per working day on STM buses.

The outskirts of Montreal are served, at peak times, by the commuter train operated by the exo transportation system. Six lines lead to downtown Montreal, Lucien-L'Allier station and Gare Centrale. There are approximately 80,000 passengers per working day on AMT trains. On , the Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec unveiled the metropolitan electrical grid project, an automated light rail system for the nearby suburbs, which is expected to be operational by 2021.

Air, rail, road and river terminals

Montreal has four major passenger terminals:

- Pierre Elliott Trudeau Airport (commonly known as Dorval), located 15 miles west of downtown Montreal, welcomes more than 18 million passengers each year: 41% for domestic flights, 59% for international flights. The 3 busiest corridors are Montreal - Toronto, Montreal - Paris and Montreal - New York;

- Montreal Bus Station, located near Berri-UQAM Metro Station, offers bus links to many cities in Quebec, Canada and the United States;

- Montreal Central Station, a train terminal near Bonaventure Metro Station, is served by Via Rail for connections to Canadian cities, and Amtrak, which provides daily connections to New York;

- the Old Port of Montreal welcomes around forty ports of call each year and over 40,000 cruise ships.

Urban cycling

Montreal is frequently cited as one of the ten largest cycling cities in the world. From May to December, 22% of Montrealers use bicycles as their main means of transport, double the Quebec average. The district with the highest proportion of bike trips is Plateau-Mont-Royal, where nearly one tenth of all bike trips are made. Apart from winter, there are daily 14,000 to 17,500 cyclists in the city center.

Montreal has a network of 650 kilometers of bicycle paths that are constantly developing. The Green Route is 80 kilometers in Montreal; the most notable sections are those along the banks of the Lachine canal, the Old Port to LaSalle and the Gilles-Villeneuve circuit.

The city of Montreal has one of the largest self-service bicycle networks, the BIXI. Since its creation in 2009, the system has been exported to more than 20 cities around the world, including London, Melbourne and New York. BIXI Montreal has 5,120 bikes spread over 450 stations, mainly in the city's central boroughs. In 2010, 3.3 million BIXI trips were registered and the network had over 30,000 subscribers.

Urbanism

Urban area: suburbs and outskirts

"Tucked into the center of the plain as the spider in the center of its web, Montreal crushes it from its mass"

— Raoul Blanchard, geographer, about Montreal.

The suburbs of Montreal are composed of 82 local municipalities grouped within the Montreal Metropolitan Community. Together, including Montreal, these municipalities cover an area of 4,360 km2 and have 4.1 million inhabitants, or nearly half of the population of Quebec. They are the 15th largest urban area in North America and the 77th worldwide. The major cities of the Montreal suburbs are Laval (422,933 hab.), Longueuil (239,700 hab.), Terrebonne (111,575 hab.), Brossard (85,721 hab.) and Repentigny (8 4285).

In recent years, as in major North American cities, urban sprawl on the outskirts of Montreal has been low-density (less than 500 people per km2). This trend involves high costs for road infrastructure, water, sewers, electricity, communications, and transportation costs. It promotes urbanization at the expense of agricultural land and natural habitats.

Layout

The layout of the lanes in Montreal is the result of the overlay of a checkerboard cut, which is very common in the major North American cities, to an older one, composed of coasts and rows, established during the French seigneurial regime.

At the end of the 17th century, Montreal was a small fortified town; its territory corresponds to the present Old Montreal. Sulpician François Dollier de Casson planned the route of the streets inside the fortifications in 1672. In the 18th century, population growth led to the creation of the first suburbs at the gates of the city; the Faubourg des Récollets at the west gate, the Faubourg Saint-Laurent at the north gate and the Faubourg Québec at the east gate.

In the 19th century, the Faubourg Saint-Laurent grew strongly, beyond the escarpment of Sherbrooke Street, thanks to the tramway. At its heart, Saint-Laurent Boulevard, a climb perpendicular to the St. Lawrence River, which crosses the island of Montreal, becomes the city's first "north-south" artery, oriented in reality north-west/south-east. In fact, by convention, East/West orientation is defined as parallel to the St. Lawrence River, throughout Quebec. Most of the development will take place from this axis, also called the "Main".

The majority of the Montreal townships were built before the second half of the 20th century. The street grid forms narrow, deep blocks of houses arranged in rows perpendicular to the St. Lawrence River. Densately populated, they are often interspersed along the length by an alley that serves the back of the buildings.

History

Hochelaga and the first explorations

Although archeologists date the first human presence in the St. Lawrence lowlands of the 4th millennium BC, the oldest artifacts found on the island of Montreal date only a few centuries before the arrival of the first European explorers.

Jacques Cartier is considered to be the first of these explorers to visit the island of Montreal. On , according to the account of his second trip to America, he landed on the island and went to the fortified Iroquoian village of Hochelaga, built at the foot of a hill called Mons realis (Mount Royal in Latin). He estimates the population of this village to be "over a thousand people".

When Samuel de Champlain, in turn, explored the river in 1603, almost 70 years later, he reported that the Iroquoians no longer occupied the Island of Montreal or the St. Lawrence Lowlands. This would be due to emigration, outbreaks of imported European diseases, and tribal wars. Hochelaga, the village described by Cartier, has disappeared. Archeological evidence strongly suggests that there have been wars with the Iroquois and Huron tribes in order to control trade routes with Europeans.

The Royal Square

In 1611, Champlain established a seasonal trading post on the Island of Montreal, at a place he named Place Royale, at the confluence of the Petite Rivière and the Saint Lawrence River (now Pointe-à-Callière). He must, however, resolve himself to abandon it, since he cannot defend it against the Mohawk warriors.

Ville-Marie and the French regime

In 1636, the island of Montreal was granted as a seigneury to Jean de Lauson, president of the Compagnie des Cent-Associés and future governor of New France. In 1640, Lauson ceded it to Jérôme Le Royer, Sieur de La Dauversière, who took possession of it on behalf of the Société Notre-Dame de Montréal and was preparing to leave for the New World.

The French colonization of Montreal really began with the establishment of the Société Notre-Dame de Montréal, a missionary colony set up to evangelize the Amerindians.

The company is led by Jérôme Le Royer de La Dauversière, Jean-Jacques Olier, Paul Chomedey de Maisonneuve and Jeanne Mance, a missionary who founded a chapel and the Montreal Hôtel-Dieu hospital.

On , Jeanne Mance arrived in Quebec City. On , Maisonneuve took over Montreal. He returned to Quebec, where, under the auspices of Pierre de Puiseaux, he wintered with 44 settlers, including four women. On , Maisonneuve was appointed Governor of Montreal. Ville-Marie was founded on .

Hard Start

"It is my honor to accomplish my mission, should all the trees on the island of Montreal be transformed into Iroquois. "

- Paul de Chomedey, Sieur de Maisonneuve, in a letter addressed to the governor of New France.

The colony had a precarious beginning. Faced with the frequent Iroquois incursions that took prisoners and killed, the fifty "montreal" settlers are often entrenched in Fort Ville-Marie. This makes agriculture difficult to practice. In addition, the Société Notre-Dame de Montréal cannot convert enough Native Americans to ensure population growth. Maisonneuve was forced to return to France to recruit other settlers in 1653 and 1659; these efforts led to nearly 200, including Sister Marguerite Bourgeoys, the founder of the Congregation of Notre-Dame de Montréal in 1659. These newcomers allow the development of agriculture, ensuring the survival and development of Ville-Marie.

In 1663, New France became a royal province. It is under the command of the Conseil Sovereign de la Nouvelle-France , which reports to Louis XIV. The Société Notre-Dame was dissolved the same year and Maisonneuve was sent back to France by Governor Prouville de Tracy. The seigneury of the Île-de-Montréal was transferred to the Séminaire Saint-Sulpice de Paris in 1665. The Sulpician priests will significantly influence the development of Montreal. The fur trade became, from 1665 onwards, a major part of the Montreal economy thanks to French military intervention. The pellets from the Ottawa River pass through Ville-Marie, which had more than 600 inhabitants at that time. The Sulpicians bordered the streets in 1672 and then the city was fortified with a pile of piles in 1687.

As Ville-Marie grows, other settlement areas appear on the island. Before the rapids of the Sault-Saint-Louis on the St. Lawrence, a fief was conceded to the explorer René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle, who founded Lachine in 1669. In Sault-au-Recollet, north of the island, on the Prairie River, a mission was founded by the Sulpicians in 1696. Despite a few periods of tranquility, the Franco-Iroquois wars wreaked havoc on the colony at the end of the seventeenth century. The bloody events include the Lashin massacre of .

Grand Peace of Montreal

In , the Montreal Treaty of the Great Peace ended hostilities. 1,200 Native Americans from some forty nations in the Great Lakes region and several New France notables, including Governor Hector de Callières, are gathering in Montreal for the signing of the treaty. The expansion of Montreal continued during the first half of the 18th century; the first suburbs appeared in the 1730s while the city has around 3,000 inhabitants. In addition to the fur trade, it becomes the central point of a growing agricultural territory.

British conquest

Begun shortly before the Seven Years' War, the War of Conquest pitted the French against the British in North America from 1754. In addition to the citadel of Montreal, at that time the French had numerous forts on the island of Montreal such as Fort Lorette, Fort de la Montagne, Fort Pointe-aux-Trembles and Fort Senneville.

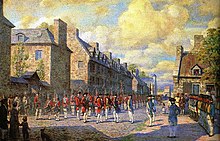

The Battle of the Plains of Abraham, a British victory in Québec City, , marked the end of the French regime on the territory. Despite a last attempt to regain the city during the Battle of Sainte-Foy on , the Duke of Lévis was forced to withdraw his troops to Montreal. On , the French troops of Montreal, commanded by Pierre de Cavagnal, Marquis de Vaudreuil, went without combat to the British army commanded by Lord Jeffery Amherst. The Treaty of Paris of 1763 marked the end of the French period.

British Regime and Industrialization

With the new regime trade became exclusively oriented towards the British Empire. Montreal, then the center of a vast hinterland, developed a solid commercial bourgeoisie, mainly of Scottish and English origin. After the war of independence of the United States and the arrival of American loyalists in the province of Quebec, the Montreal region became a buffer where two peoples, one Anglophone and Protestant, the other Francophone and Catholic.

Political unrest

Although the Canadians (descendants of the first French settlers) were the majority, their political underrepresentation and the denial of their language created a situation of tension culminating in the rebellion of the Patriots of 1837-1838. Montreal is the site of riots on both sides of the population. The United Canada Parliament, established in Montreal between 1843 and 1849, was burned by anti-unionist rioters called to arms by a hate article in The Gazette. The fire also spread to the National Library, destroying countless archives of New France. These incidents prompted Members of the United Canada to move the capital alternately to Toronto and Quebec City, and then to choose Ottawa from 1866.

Industrial Revolution

Economically, the early 19th century marked an important transition in Montreal's commercial activity. Its geographical position linked to natural communication networks already made the city an important center of the fur trade to Europe. The beginning of the British colonization of Upper Canada by the Loyalists turned Montreal into a hub for the supply and settlement of the Great Lakes region. The fur trade industry — which has dominated economic activity for more than a century — is losing importance in relation to trade and transportation. The city’s growth accelerated by the construction of the Lachine Canal in 1824, allowing ships to cross the Lachine rapids and facilitating communication between the Atlantic and the Great Lakes.

The second half of the 19th century brought about the rapid development of the railway, the creation of a first 23 km railway line between Laprairie and Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu in 1836, and the canal de Chambly, inaugurated in 1843. Both infrastructure improve communication with New York, via Lake Champlain or its shoreline and the Hudson River Valley. The construction of the Grand Trunk lines to Toronto and the maritime provinces in the 1850s, and the Victoria Bridge in 1860, reinforced the city's vocation. The Canadian Pacific Railway Company established its head office in 1880, making Montreal Canada's railway node. At the same time, the craft industry is giving way to industrialization.

The city suffered several epidemics during the 19th century, the largest being the smallpox epidemic of 1885, which killed 3,164 people (the vast majority of Francophones), or 1.89% of its population estimated at 168,000.

Between the epidemics and the great fires, the commercial elite, which became industrial, began to settle in the Golden Square Mile. In 1860, Montreal became the largest municipality in British North America and the economic and cultural center of Canada.

Apogee and Relative Decline

Between the late 19th century and the outbreak of the First World War, Montreal experienced one of the strongest periods of growth in its history. The development of banks and other financial institutions with industry provides the impetus to become Canada's financial center for the first half of the 20th century.

After the war, the city modernized and developed a reputation as a festive city. Prohibition in the United States makes it a popular destination for Americans. The rise of beverage flows, cabarets, gaming houses, betting networks, easy access to drugs, the abundance of brothels, the rise of sex tourism, combined with a growing influence of the underworld, as well as a certain connivance of the police forces, led to the call of the "open city".

Despite Montreal's growth, unemployment persists there and is exacerbated by the 1929 crash. During the Great Depression, the city helped the unemployed and undertook a major labor policy that hit its finances so hard that it was placed under the provincial government from 1940 to 1944. During this period, the war effort brought full employment and ushered in a new era of prosperity.

Competition with Toronto

In 1951, the population of Montreal exceeded one million. Yet Toronto's growth has already begun to challenge its status as Canada's economic capital. Indeed, since the 1940s the volume of shares traded on the Toronto Stock Exchange has become greater than that of the Montreal Stock Exchange. The 1950s and 1960s were marked by sustained growth, symbolized by the holding of the 1967 Universal Exhibition, the construction of the highest Commonwealth towers, the motorway network and the Montreal subway. Yet Montreal's economy, since the end of the Second World War, has been changing. A vast movement of industries to the Midwest and southern Ontario, combined with technological changes, such as the development of trucking and the commissioning of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1959, is gradually reducing Montreal's importance as a center for freight transshipment.

Quiet revolution

The 1970s turned out to be a period of vast social and political changes, emanating from a Francophone majority ending its Quiet Revolution in the face of the traditional dominance of the business world by an Anglophone minority eroded by the slow decline of their city. The crisis of October 1970, when the army was deployed in the streets, and the election in 1976 of the Parti Québécois, a proponent of sovereignty, led to the departure of large companies (Sun Life, RBC...) and many of the city's people, further accelerating the overthrow of the hierarchy of Canadian metropolises in favor of Toronto. However, this does not prevent Montreal, led by Mayor Jean Drapeau, from securing its international status by becoming an Olympic city in the same year of 1976. The metropolis is at its peak, at the cost of a large debt.

Contemporary Montreal

Until the mid-1990s, the Montreal economy, hit hard by the recessions of 1981-82 and 1990-92, grew more slowly than many Canadian cities. A major industrial restructuring and a development of cultural industries will give the city a second breath. Montreal celebrates its 350th anniversary in 1992.

The city was hit in by the first mass femicide. A man declaring his dislike of "feminists" kills fourteen young women at the Polytechnic.

Merger-defusion

On ,, Montréal was merged with 27 neighboring municipalities, creating a unified city covering the entire island of Montreal. However, the English-speaking suburbs[necessary context] perceive this merger as imposed by the Parti Québécois and, following the election of a Liberal government in Quebec, several municipalities are voting to leave the unified city through referenda in . Partial de-fusion takes place on , leaving 15 municipalities on the island, including Montreal. The 2002 mergers were not the first in the city's history. In fact, Montreal previously annexed 27 other towns and villages, starting with Hochelaga in 1883, until Pointe-aux-Trembles in 1982.

The 21st century brings about a revival of the city's economic and cultural landscape and infrastructure. The construction of residential skyscrapers, two superhospitals, the Quartier des Spectacles, the gentrification of Griffintown, the expansion of the Montréal-Trudeau airport, the replacement of the Champlain Bridge by the Samuel-De Champlain Bridge, the reconstruction of the Turcot interchange and the Metropolitan Express Transit project are all achievements that make Montreal continue to grow.

Policy and Administration

Municipal Administration

Montreal is a city municipality governed by an independent charter. Its municipal government is divided into three levels: the city, the boroughs and the city.

Municipal political parties

Montreal officially has eight political parties according to Elections Québec's official data:

- Montreal Coalition

- Montreal Ensemble

- Montreal Project - Team Valérie Plante

- Real change for Montreal

- Anjou Team

- Team Barb Team

Municipal Council

The Montreal City Council is the city's main decision-making body. It is composed of 65 members: the mayor, the 19 mayors of the borough and 46 city councilors. The mayors of the district are elected by universal suffrage from the population of their district and the councilors of the city are elected by a majority vote in the various electoral districts of the city (each district is divided between 0 and 4 electoral districts).

Mayor

The mayor is elected by a single-member majority vote every 4 years. It embodies the executive power within the city's municipal administration; in addition to the city council, he sits on the city council and the executive committee of Montreal. He is also mayor of the Ville-Marie borough.

- Recent Mayors

- Following the resignation of Mayor Gérald Tremblay on , Michael Applebaum was appointed interim mayor until the municipal election. Following criminal charges relating to a corruption case, he was replaced by Laurent Blanchard on , with an election to the city council;

- On , Denis Coderre was elected;

- On , a Montreal mayor was elected, Mrs. Valérie Plante.Montreal's current mayor, Valérie Plante.

Board committees

Eleven standing committees of the council deal with public consultations and the receipt of comments and criticisms related to their respective fields. Above all, they are consultation bodies, and therefore not decision-making bodies, unlike the Executive Committee. Their mission is to inform and inform the choice of members of the city council and to encourage citizen participation in public debates.

"The composition of the standing committees varies between them. Each is composed of a number of 7 to 12 elected as the case may be. One of them is designated to act as Chair and at least two others act as Vice-Chairs. With the exception of the Commission de la Presidency du Conseil, which makes recommendations strictly to the city council, two members of each commission are chosen from the members of the councils of the related municipalities to occupy one of the vice-presidencies (metropolitan component). The term of office of the members of the standing committees is determined by the city council and the city council.Only the term of office of the person representing the government of Quebec on the Public Safety Commission is determined by the government of Quebec. Finally, one person accompanies the work of each standing committee as a research secretary. "

- Information guide (): standing committees of the city council and agglomeration

Arrondissements

The city of Montreal has 19 arrondissements. Many of them are former cities merged in Montreal. The boroughs are headed by the borough council composed of the mayor of the arrondissement, the city councilors of the arrondissement and the arrondissement councilors, if any (the boroughs elect between 0 and 3 arrondissement councilors). In total, the 19 boroughs include 39 arrondissement councilors. They are responsible locally for town planning, waste removal, culture, recreation, community development, parks, highways, housing, staff, fire prevention, financial management and non-tax fees.

| No | Name | Area (km2) | Population (2016) | Density inhabitants / km2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ahuntsic-Cartierville | 24.2 | 134,245 | 5,547.3 |

| 2 | Anjou | 13.7 | 42,796 | 3,123.8 |

| 1 | Côte-des-Neiges-Notre-Dame-de-Grâce | 21.4 | 166,520 | 7,781.3 |

| 4 | Lachine | 17.7 | 44,489 | 2,513.5 |

| 5 | LaSalle | 16.3 | 76,853 | 4,714.9 |

| 6 | The Plateau-Mont-Royal | 8.1 | 104,000 | 12,839.5 |

| 7 | The Southwest | 15.7 | 78,151 | 4,977.8 |

| 8 | Ile-Bizard-Sainte-Geneviève | 23.6 | 18,413 | 780.2 |

| 9 | Mercier-Hochelaga-Maisonneuve | 25.4 | 136,024 | 5,355.3 |

| 10 | Montreal North | 11.1 | 84,234 | 7,588.6 |

| 11 | Outremont | 3.9 | 23,954 | 6,142.1 |

| 12 | Pierrefonds-Roxboro | 27.1 | 69,297 | 2,557.1 |

| 13 | Rivière-des-Prairies-Pointe-aux-Trembles | 42.3 | 106,743 | 2,523.5 |

| 14 | Rosemont-La Petite-Patrie | 15.9 | 139,590 | 8,779.2 |

| 15 | St. Lawrence | 42.8 | 98,828 | 2,309.1 |

| 16 | Saint-Léonard | 13.5 | 78,305 | 5,800.0 |

| 17 | Verdun | 9.7 | 69,229 | 7,137.0 |

| 18 | Ville-Marie | 16.5 | 89,170 | 5,404.2 |

| 19 | Villeray-Saint-Michel-Parc-Extension | 16.5 | 143,853 | 8,718.4 |

| TOTAL | 365.2 | 1,704,694 | 4,667.8 | |

Agglomeration

On the Island of Montreal, the city of Montreal and the 15 "de-merged" municipalities since 2006 are located on the Montreal Metropolitan Council. This council manages the powers of agglomeration throughout the territory of the Island of Montreal, including public safety, land assessment, distribution of drinking water, wastewater and waste treatment, roads and public transportation. desired]. It is composed of the Mayor of Montreal, 15 councilors from Montreal and 14 mayors and 1 representative of the reconstituted cities of the Island of Montreal.[ref. Desired] The "de-merged" cities retain the skills of proximity (leisure, public works, etc.).

Non-municipal governments

Provincial Representation

At the provincial level, representation in the National Assembly of Quebec is made by elected members in constituencies. Twenty-seven electoral districts are located in Montreal (although some of them overlap Montreal and other cities).

- Acadia (Christine St-Pierre, PLQ)

- Anjou-Louis-Riel (Lise Thériault, PLQ)

- Bourassa-Sauvé (Paule Robitaille, PLQ)

- Bourget (Richard Campeau, CAQ)

- D'Arcy-McGee (David Birnbaum, PLQ)

- Gouin (Gabriel Nadeau-Dubois, QS)

- Hochelaga-Maisonneuve (Alexandre Leduc, QS)

- Jacques-Cartier (Gregory Kelley, PLQ)

- Jeanne-Mance-Viger (Filomena Rotiroti, PLQ)

- LaFontaine (Marc Tanguay, PLQ)

- Laurier-Dorion (Andrés Fontecilla, QS)

- Marguerite-Bourgeoys (Hélène David, PLQ)

- Marquette (Enrico Ciccone, PLQ)

- Maurice-Richard (Marie Montpetit, PLQ)

- Mercier (Ruba Ghazal, QS)

- Mont-Royal-Outremont (Pierre Arcand, PLQ)

- Nelligan (Monsef Derraji, PLQ)

- Notre-Dame-de-Grâce (Kathleen Weil, PLQ)

- Pointe-aux-Trembles (Chantal Rouleau, CAQ)

- Robert-Baldwin (Carlos J. Leitão, PLQ

- Rosemont (Vincent Marissal, QS)

- Saint-Henri-Sainte-Anne (Dominique Anglade, PLQ)

- St. Lawrence (Marwah Rizqy, PLQ)

- Sainte-Marie-Saint-Jacques (Manon Massé, QS)

- Verdun (Isabelle Melançon, PLQ)

- Viau (Frantz Benjamin, PLQ)

- Westmount-Saint-Louis (Jennifer Maccarone, PLQ)

Federal Representation

At the federal level, representation in the House of Commons of Canada is made by elected members in constituencies. Eighteen electoral districts are located in Montreal (although some of them overlap Montreal and other cities).

- Ahuntsic-Cartierville (Melanie Joly, PLC)

- Bourassa (Emmanuel Dubourg, PLC)

- Dorval—Lachine—LaSalle (Anju Dhillon, PLC)

- Hochelaga (Soraya Martinez Ferrada, PLC)

- Honoré-Mercier (Pablo Rodriguez, PLC)

- La Pointe-de-l'Île (Mario Beaulieu, Bloc québécois)

- Lac-Saint-Louis (Francis Scarpaleggia, PLC)

- LaSalle—Émard—Verdun (David Lametti, PLC)

- Laurier—Sainte-Marie (Steven Guilbeault, PLC)

- Mount Royal (Anthony Housefather, PLC)

- Notre-Dame-de-Grâce—Westmount (Marc Garneau, PLC)

- Outremont (Rachel Bendayan, PLC)

- Papineau (Justin Trudeau, PLC)

- Pierrefonds—Dollard (Sameer Zuberi, PLC)

- Rosemont-La Petite-Patrie (Alexandre Boulerice, NDP)

- Saint-Laurent (Emmanuella Lambropoulos, PLC)

- Saint-Léonard—Saint-Michel (Patricia Lattanzio, PLC)

- Ville-Marie—Southwest—Île-des-Soeurs (Marc Miller, PLC)

Representation in the Senate of Canada is made by senators appointed in divisions. Three senatorial divisions are located in Montreal (although some overlap Montreal and other cities).

- Alma (Diane Bellemare, GSI)

- Rigaud (Vacancy)

- Victoria (Jean-Guy Dagenais, GSC)

Twinning and international agreements

| Country | City | Region/State | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Montreal-la-Cluse | Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes | 1970 | |

| Montreal-les-Sources | Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes | 1972 | |

| Montreal-du-Gers | Occitania | 1983 | |

| Shanghai | Shanghai | 1985 | |

| Lyon | Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes | 1989 | |

| Boston | Massachusetts | 1995 | |

| Port-au-Prince | West | 1995 | |

| Tel Aviv-Jaffa | Tel Aviv District | 1996 | |

| Beihai | Guangxi | 1996 | |

| Milan | Lombardy | 1996 | |

| Athens | Athens Center | 1997 | |

| Hanoi | Hanoi | 1997 | |

| Santiago | Santiago | 1997 | |

| Moscow | Central | 1997 | |

| Quito | Pichincha | 1997 | |

| Hiroshima | Chūgoku | 1998 | |

| Yerevan | Yerevan | 1998 | |

| Alger | Alger | 1999 | |

| Tunis | Tunis | 1999 | |

| Casablanca | Casablanca-Settat | 1999 | |

| Busan | Busan | 2000 | |

| San Salvador | San Salvador | 2001 | |

| Managua | Managua | 2001 | |

| Paris | Île-de-France | 2006 | |

| Bamako | Bamako | 2008 |

Population and society

Gentile

The Montrealer, Montrealer is used to designate the inhabitants of Montreal. This French name was formalized in the spring of 2015. According to a Quebecois linguist, Montrealer has as its equivalent Montrealer in English, pictures in English, pictures in Arabic, Montrealés, montrealesa in Spanish, Montrealese in Italian and 蒙 特 利 尔 人 in Chinese.

Demographics

Montreal is the most populous city in Quebec, Canada's second most populous city and the center of a city of nearly 4 million people. In 2016, there were 1,704,694 Montrealers. The average population density in the city is 4,662 inhabitants/km2. It reaches 13,096 inhabitants/km2 in Plateau-Mont-Royal and 18,802 inhabitants/km2 in Parc-Extension.

Immigration is the main driver of Montréal's population growth. Between 2008 and 2009, the Island of Montreal welcomes 40,005 new international immigrants. For the same period, natural increment brings 8,235 new Montrealers.

The city's population is relatively young: in 2006, according to Statistics Canada, the percentage of residents under 35 is 44%, 2 points higher than the Quebec average of 41.8%. The median age is 38.8 years, slightly below the provincial average (41 years).

Demographic evolution

The population of the City of Montreal grew during the second half of the 19th century and during the first half of the 20th century. During this period, the city's population, not to mention the suburbs, increased from a little less than 60,000 inhabitants to more than one million; Montreal was Canada's most populous city until the 1950s.

In addition to Irish immigration during the nineteenth century, industrialization is the main factor in the city's growth. The inhabitants of the surrounding countryside migrate to the city to work in the factories. Most of the arrivals are French Canadians and English Canadians from rural Quebec, Ontario and New Brunswick.

Immigration and ethnic groups

| Ethnic origin | Population | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 1,670,655 | 43.8% | |

| 870,245 | 21.7% | |

| 279,800 | 7.0% | |

| 239,460 | 6.0% | |

| 138,320 | 3.4% | |

| 132,255 | 3.3% | |

| 124,130 | 3.1% | |

| 108,775 | 2.7% | |

| First Nations | 101,915 | 2.5% |

| 95,784 | 2.4% | |

| 92,115 | 2.3% | |

| 86,025 | 2.1% | |

| 77,450 | 1.9% | |

| 68,600 | 1.7% | |

| 66,395 | 1.7% | |

| 68,765 | 1.7% | |

| 64,895 | 1.6% | |

| 56,405 | 1.4% | |

| 49,275 | 1.2% | |

| 48,485 | 1.2% | |

| 47,980 | 1.2% | |

| 38,660 | 1.0% | |

| 35,685 | 0.9% | |

| 35,050 | 0.8% | |

| 31,840 | 0.8% |

The population of European origin is overwhelmingly of French, Irish, English and Italian ancestry, according to Statistics Canada. The four major ethnic groups on the Island of Montreal were, in 2001, Canadians (a multi-generational population in Canada) at 55.7% (1,885,085), French at 26.6% (900,485), Italians at 6.6% (224,460) and Iranians. Latino at 4.7 % (161 235).

In the city of Montreal, again in 2001, the descendants of Canadian Francophones or Anglophones of British and French ancestral identity were the majority. Those identified as Canadians of so-called ancestral identity under Canada's Official Languages Act are predominantly of French, Irish, English and Scottish descent, or their families who have been living on the territory for generations.

In 2016, the main visible minorities were, in order of importance, Afro-Canadians who accounted for 9.5% of the total population and Arabs for 6.9%, an increase of 17% compared to 2011[ref. not compliant].

Cultural communities

The distribution of Montreal's cultural communities varies greatly with the boroughs. More than 200 communities are present, having established their neighborhoods as early as the seventeenth century, or as recently as the twenty-first century.

Languages

40-90% French

40-70% English

40-60% allophone

- 30-40% Franco-Anglo

- 30-40% Franco-Allo

- 30-40% Anglo-Allo

- +30% Equality

According to 2006 Census data, the majority of residents of the Montreal metropolitan community (about 65%) have French as their mother tongue, a significant share (23%) of the population is New-Canadian, having neither English nor French as their mother tongue, while about 12% report that they are English.

According to the same source, on the whole of the island of Montreal, the situation is changing, while about 50% of the population declares themselves French, 34% allophone and 16% anglophone. However, the majority of citizens have at least a practical knowledge of the majority language and most Allophones have French or English as their second language. Almost 53% of Montrealers are bilingual French and English, 29% of people speak only French, and 13% of Montrealers speak only English (mostly concentrated in the West of the Island of Montreal).

Some people are unable to communicate in either English or French. However, the tendency of new immigrants to learn the majority language has accelerated since the introduction of the French Language Charter in the 1970s. Italian, Portuguese, Spanish and Romanian are the other Romanesque languages used in Montreal; German, Greek, Yiddish but also Berber (kabyle), Arabic, Mandarin, Cantonese, Vietnamese, Haitian Creole and Hindi are also languages used in Montreal (due to immigration). The use of French at home, in general, has increased in the Montreal metropolitan community. The Anglophone population continued to decline from 1996 to 2001. Its share rose from 13.7% in 1996 to 12.8% in 2001 and 11.8% in 2011[ref. desired]. The proportion of Francophones increased slightly during this five-year period, from 67.9% to 69.1%[ref. desired], then 85.7% of people who can speak French in 2011.

Moreover, the 2006 statistics show a reversal of the trend. Indeed, all boroughs in the city have seen their proportion of Francophone speakers decrease since 2001. In five years, this variation varies by district, ranging from a 1% increase in Loyola (borough of Côte-des-Neiges-Notre-Dame-de-Grâce) to a 29% decrease in Sainte-Geneviève (borough of L'Île-Bizard-Sainte-Geneviève). The regression of French in the city of Montreal is a recurring topic in Quebec French-language media. However, it must be nuanced to the extent that this percentage decline is not in favor of a single language but of a multitude of languages, as a result of the reception of a large number of native-speaking immigrants other than French and English. On the other hand, French remains the majority working language (66.5% of the unique responses to the 2006 census).

Canadian Capital of Trilingualism

The Canadian capital of bilingualism for a long time, Montreal is now recognized as the capital of trilingualism in Canada thanks to the presence of multilingual immigrants. New Montrealers are more than 44% trilingual, while Montreal natives, both French and English, are only 3% trilingual. The Quebec metropolis is thus the Canadian capital of trilingualism thanks to its new citizens and its linguistic reality is changing. The phenomenon will accelerate over the next few years with immigration aimed at reducing the low fertility rate.

Officially, Arabic is the third language spoken on the Island of Montreal after French and English. Speakers of Arabic at home are estimated to be 160,000 to 140,000 Spanish speakers[ref. not compliant]. However, these figures do not take into account the attractiveness of Spanish to native Montrealers who travel or learn the language of Cervantes. According to the sociologist Victor Armony (2017), Spanish is already the third most spoken language in Quebec, with 350,000 speakers saying that they can maintain a conversation in Spanish compared to 210,000 in Arabic. In fact, the 2016 census states that 280,000 Montrealers reported having some knowledge of Spanish, compared to only 241,000 for Arabic.

Religions

According to 2011 Statistics Canada data, Montreal is a predominantly Catholic city; 53% of the population adheres to this Christian faith. Montrealers without religious affiliation are the second largest group, representing 18% of the population. The other three major groups are Muslims, Orthodox and Protestants. Montreal also hosts smaller Buddhist, Sikh, Baha'i, Jehovah and Hindu communities.

Christianity

When he visited the city in 1881, American writer Mark Twain called Montreal the "city with a hundred bell towers". This illustrates the large number of Roman and Protestant Catholic churches in the city. The Archdiocese of Montreal alone has more than 200 active parishes now[When?].

Catholic

The Catholic Christians of the metropolis are part of the Archdiocese of Montreal[ref. not in conformity], whose archbishop is attached to the basilica-cathedral of Mary Queen of the World. The city has several other important Catholic places of worship, such as St. Joseph's Oratory, the most important pilgrimage site dedicated to St. Joseph, Notre Dame Basilica and St. Patrick's Basilica. Traditionally Catholic, the Notre-Dame-des-Neiges Cemetery, located on the northern flank of Mount Royal, is Canada's largest cemetery. The Catholic Church finds the majority of its faithful in the Canadian-French majority and communities of Irish, Italian, Portuguese, Polish and Haitian origin. There are also several Eastern Catholic communities, close to the Orthodox.

Protesters

Historically associated with Anglo-Quebecers, the Montreal Protestants are mainly Anglicans. The latter are part of the Anglican Diocese of Montreal, whose headquarters are located at Christ Church Cathedral[ref. not compliant]. The United Church of Canada, the most important Protestant denomination in the country, has as its place of worship the United Church of Saint James. On the evangelical side, the first Baptist church was established in the city in 1831 by John Gilmour, an English pastor. Founded in 1916, the Evangel Pentecostal Church is the first Pentecostal Church in Montreal and Quebec. The Mont-Royal Cemetery has traditionally served the Protestant community.

Orthodox

Orthodox Christianity has the majority of its members among the Greek, Russian, Romanian and Arab communities. For example, there is the St. George Orthodox Church, a National Historic Site of Canada.

Christian Lépine is the Catholic Archbishop of Montreal.

Christ Church Cathedral is the seat of the Anglican Diocese of Montreal.

The Evangel Pentecostal Church building in the city center.

The Antiochian Orthodox Church of Saint George.

Islam

Almost absent before the second half of the 20th century, Islam has grown strongly in Quebec since the elimination of racial discrimination in Canadian immigration policies in 1962. There are now[When] more Muslim practitioners than Catholic practitioners in Montreal. Between 2001 and 2011, the Muslim population nearly doubled in the city, from 81,000 to 155,000 believers in the space of 10 years. This trend is mainly due to immigration from Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia and Lebanon. Unlike France, Germany, or the United Kingdom, there is no domination of a particular Muslim ethnic group in Montreal; 70% of Muslims are Sunni and 30% are Shia. Just over fifty Muslim places of worship exist in the greater Montreal region.

Judaism

The Jewish community (lay Jews and practicing Jews) of Montreal, established mainly in the early twentieth century, is mainly concentrated in the districts of Outremont, Côte-des-Neiges-Notre-Dame-de-Grâce and Saint-Laurent; around the landlocked towns of Côte-Saint-Luc and Hampstead, where the Jews are the majority. There are 80,000 Jews in the city of Montreal and more than 120,000 on the island.

Geographically close to Montreal is the Jewish Hassidic community Kiryas Tosh de Boisbriand.

Civil Society and Civil Rights

With its lively neighborhood, the Village, the largest gay neighborhood in North America and one of the largest in the world, Montreal is one of the poles of gay and lesbian life in Canada. Between 1999 and 2000, Montreal was chosen to be part of the select group of gay capitals worldwide, including, in 1999, the cities of Montreal, Paris, Munich, Manchester, Sydney and, in 2000, Amsterdam, Berlin, Manchester. In 2006, it hosted the first World Outgames (LGBT Olympic Games).

Sports

Montrealers practice several types of sports activities on a recreational basis thanks to the presence of numerous amateur sports clubs and local sports associations. The popularity of sports is also enhanced by the existence of a network of outdoor fields and indoor facilities (arena, gym, indoor soccer field). In winter, ice rings and ice rinks are set up outside. The Castors Lake on Mount Royal and the ice ring in the old port allow Montrealers to return to skating in a family atmosphere. Cross-country skiing is also a popular activity and several hundred kilometers of marked trails are maintained by the city in the parks.

Sports Events

Throughout its history, Montréal has hosted several major sporting events, including the 1976 Summer Olympics, the 1967 World Fencing Championships, the 1967 World Track Cycling Championships, the 1974 Road Cycling Championships, the 1984 Rowing Championships, and the 2005 Swimming Championship. Rogers Tennis Cup, the Formula 1 Grand Prix of Canada.

Olympic Games:

- 1976 Summer Olympics.

Car Race:

- Formula 1 Grand Prix of Canada (on the Gilles-Villeneuve circuit) from 1978 to 2008. After a break in 2009, the Grand Prix of Canada has been held again since 2010;

- Nascar Nationwide Series (on the Gilles-Villeneuve circuit), from 2007 to 2012;

- Nascar Canadian Tire Series (on the Gilles-Villeneuve circuit), since 2007.

Cycling:

- 1974 UCI Road and Road World Championships;

- Montreal Women's World Cup, since 1998;

- Tour of the Island of Montreal, since 1985;

- Grand Prix cycliste de Montréal (Pro Tour de l'UCI), since 2010.

Golf:

- Montreal Championship of the Champions Tour of the PGA settled in Montreal in 2010 and for several consecutive years (There have already been editions of 1904, 1908, 1913, 1926, 1935, 1946, 111 950, 1956, 1959, 1967, 1997 and 2001 — but never a Montreal tournament for several years);

- 7th Presidents Cup, 27-.

Marathon:

- Marathon of Montreal, created in 1979. Discontinued in 1990, the event was resumed in 2003. Since 2012 the race has been run by Competitor Group, Inc. (en) as part of the Rock 'n' Roll Marathon Series. The Montreal Oasis Marathon (current name according to the name of the sponsor) includes the marathon, the half-marathon and several secondary competitions.

Swimming:

- XIth FINA World Swimming Championships from 17 to .

Soccer:

- 2007 FIFA Under-20 World Cup (10 matches in July 2007);

- 2015 Women's World Cup (9 matches).

Tennis:

- Tennis Masters of Canada, since 1989. In even years Montreal receives women (WTA), while in odd years Montreal receives men (ATP), alternating with Toronto. In 2009, the Rogers Cup tournament set a record of attendance, becoming the first one-week tournament to attract a crowd of more than 200,000 spectators. It was also the first time that the top eight players in the world, according to the ATP ranking, were all in quarterfinals.

Quebec Games:

- Montreal hosted the Quebec Games in the winters of 1972, 1977, 1983 and the summers of 1997, 2001 and 2016.

Global Outgames:

- Montreal hosted the first World Outgames from to as Rendez-vous Montréal 2006.

Major sports teams

Professional sport in Montreal is an essential dimension of Montreal's integration into the North American continent. Montreal has several professional sports teams that are franchises of large continental leagues.

Major sports allowances:

| Club | League | Speaker | Foundation | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Montreal Canadians | NHL (Ice Hockey) | Bell Center | 1909 | 24 (23 NHL,1 Before the NHL) |

| Impact of Montreal | First USL Division (1993-2011) MLS (2012-) (soccer) | Saputo Stadium | 1993 | 3 USL Cup / 10 Canadian Championship |

| Montreal Alouettes | CFL (Canadian Football) | Percival-Molson Stadium | 1946 | 7 |

| Royal of Montreal | American Ultimate Disc League (ultimate ) | Claude-Robillard Sports Complex | 2014 | 0 |

Major past deductions:

| Club | League | Speaker | Existence | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Montreal Exhibition | MLB (baseball) | Olympic Stadium of Montreal | 1969-2004 | 0 |

| Maroons of Montreal | LNH | Montreal Forum | 1924-1938 | 2 |

| Manic of Montreal | North American Soccer League (LNAS) | Olympic Stadium | 1981-1983 | 0 |

| Montreal Express | National League of Crosses | Bell Center | 2004 | 0 |

| Roadrunners of Montreal | National League of Roller Hockey | Molson Center | 1996-1999 | 0 |

| Montreal machine | World League of American Football | Olympic Stadium | 1991-1992 | 0 |

Health

The Montreal Health and Social Services Network has 10 institutions: 5 Integrated University Health and Social Services Centers (CIUSSS) and 5 unmerged institutions.

Integrated Health and Social Services Centers

As their names indicate, CIUSSS is a public body responsible for providing social care and services in a given region. In addition to hospital centers, they include long-term care and accommodation centers, local community service centers, child and youth protection centers and rehabilitation centers.

| CIUSS | Major health facilities |

|---|---|

| Center-Ouest-de-l'Île-de-Montréal [11] | Jewish General Hospital |

| Center-Sud-de-l'Île-de-Montréal [12] | Montreal Chinese Hospital, Montreal University Geriatric Institute, Raymond-Dewar Institute |

| West Island of Montreal | Sainte-Anne Hospital, Douglas Mental Health University Institute |

| Nord-de-l'Île-de-Montréal | Montreal Sacred Heart Hospital |

| East of Montreal Island | Montreal University Institute of Mental Health, Maisonneuve-Rosemont Hospital |

Non-merged institutions

McGill University Health Center (CUSM)

Founded in 1997 as the merger of several bilingual hospitals, the MUHC employs 1,587 doctors, dentists and pharmacists, 2,715 researchers and teachers, and receives over 700,000 patients each year. The main facilities are located within the Glen Superhospital, built in 2015.

- Site Glen, 500 beds, where the following hospitals are grouped:

- Montreal Children's Hospital;

- Royal Victoria Hospital;

- Montreal Thoracic Institute.

- Satellite hospitals:

- Montreal General Hospital;

- Montreal Neurological Institute;

- Lachine Hospital and Camille-Lefebvre Pavilion.

UdeM Hospital Center (CHUM)

The CHUM employs 881 doctors, 1,300 researchers and teachers and receives over 500,000 patients in hospital each year. Since 1995, it has included the following predominantly French-speaking hospitals:

- The town center site, 772 beds and 39 operating rooms, opened in 2017, includes:

- the Hôtel-Dieu de Montréal, the city's first hospital, founded in 1645;

- Saint Luke Hospital;

- Notre-Dame Hospital.

- Partner Hospitals:

- Montreal Heart Institute;

- Philippe Pinel Institute of Montreal;

- Sainte-Justine University Hospital, one of the largest children's hospitals in North America.

Education

Montreal is consistently at the top of the world's best student cities. For example, in 2013, according to The Economist, Montreal ranked first in the world as a destination for overseas studies, ahead of London. According to QS Best Student Cities 2017, Quebec's metropolis would be the best city in the world to study. With more than 170,000 students, the city ranks second among North American metropolises in the number of university students per capita. In 2011, more than 60% of the Montréal population held a post-secondary certificate, diploma or grade.

Primary and secondary education

In 1658, Marguerite Bourgeoys founded a first Catholic school on the current rue Saint-Dizier in Old Montreal.

The city has approximately 250,000 students (80% in the Francophone system) in a total of 268 primary schools (233 Francophones and 35 Anglophones), 75 secondary schools (58 Francophones, 16 Anglophones and 1 Bilinguals), 26 centers for adult education (14 Francophones and 12 Anglophones) 37 specialized schools. The administration of these educational institutions is shared by five school boards, three of which are French (f) and two English (a):

- Montreal School Board (f) 110,345 students (40%);

- the Marguerite-Bourgeoys school board (f) 53 000 pupils (20%);

- Pointe-de-l'Île school board (f) 44,224 students (20 per cent);

- Lester B. Pearson School Board (a) 20,000 students (10 per cent);

- the English-Montreal School Board (a) 19,000 students (10%).

Higher education

With four universities, seven higher institutions, and 12 CEGEPs within a radius of 8 kilometers, Montreal would have the largest concentration of post-secondary students among the major cities of North America (4.38 students per 100 inhabitants in 1996, followed by Boston with 4.37).

Collars

Quebec's educational system is different from other North American systems. After high school (which ends in the eleventh year) students can continue in colleges of general and vocational education (CEGEP), offering pre-university (2 years) and technical (3 years) programs. In Montreal, 17 CEGEPs offer courses in French and 5 in English. In addition to these public institutions, Montreal has nine private colleges and two college-level vocational training institutions.

Francophone Universities

- The Université de Montréal (UdeM) is one of Canada's ten major universities. It is the first Canadian French-speaking university and the second largest in the world after the Sorbonne in France[ref. desired]. According to the Times Higher Education Supplement, it is one of the top 100 universities in the world. The Université de Montréal has two affiliated university schools, HEC Montréal and Polytechnique Montréal, both located on campus. The Center hospitalier de l'Université de Montréal (CHUM), moved to the city center, brings together the hospitals affiliated to the university with the new Center de recherche du Center hospitalier de l'Université de Montréal (CRCHUM);

- The Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM) is part of the Université du Québec's public network. Its main campus is located in the heart of the Latin Quarter, near Saint-Denis and Sainte-Catherine Streets, while the buildings housing the Faculty of Science are located a little to the west near Saint-Urbain Street. The École des sciences de la gestion (ESG), the École de design and the École supérieure de mode de Montréal are some of the components of the university. In addition, the École nationale d'administration publique (ÉNAP), the TÉLUQ, the École de technologie supérieure (ÉTS) and the Institut national de la recherche scientifique (INRS) are more of the constituent institutions of the University of Quebec's network.

English Universities

- The McGill University, with a more traditionalist than avant-garde reputation[ref. desired], is one of the oldest and most prestigious universities in Canada[ref. desired]. In 2015, it was ranked the top Canadian university for the eleventh consecutive year by Maclean's and 24th globally by the world ranking of QS universities. McGill University is located in the heart of the city center, close to the McGill ghetto, a neighborhood with a large student population. She is associated with the Marianopolis College for her music program. The Royal Victoria Hospital, formerly located on campus, is part of the McGill University Health Center, along with the Montreal General Hospital and the Jewish General Hospital. In addition to its downtown Montreal campus, the University holds the Macdonald campus in the West Island of Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue.

- The Concordia University, with a more modern reputation and open to all, is officially bilingual: students can deliver their work and write their exams in french or english. Concordia is currently expanding, with the construction and acquisition of new buildings, including the modern IT, electrical engineering and arts pavilion, as well as the historic building of the former convent of the Gray Sisters. Concordia University is composed of the Sir-George-Williams campus in downtown Montreal (Guy-Concordia subway station) and the Loyola campus in the residential neighborhood of Notre-Dame-de-Grâce (Vendôme subway station).

Economy

Canada's second largest metropolis, Montréal is a major cultural, industrial, commercial and financial center, whose prosperity is based "on sustained exchanges of goods with regional and international markets."

The city and its immediate area have the most diversified economy in Canada. Montreal's industries include telecommunications, aeronautics, pharmaceuticals, high technology, graduate studies, video games, textiles, fashion, electronics, transportation equipment, tobacco and printing. Major or particularly well-known companies in the Montreal area include Bombardier, Hydro-Québec, BCE, Power Corporation, Canadian National, National Bank of Canada, Air Canada, Rio Tinto Alcan, SNC-Lavalin, Saputo, CGI, Québecor, Domtar, Air Transat, Transcontinental and Metro Richelieu.

Primary sector

With urban sprawl, arable land disappears from Montreal, except to the far west of the island where a 191ha agricultural park is preserved. Greenhouse agriculture on the city's rooftops is developing with civic or business initiatives like the Lufa Farms since 2011. Until the 1930s, Montreal had several limestone quarries. Those that are not backfilled are converted to landfills or snow deposits. Only the 1910 Lafarge aggregate quarry of Montreal East is still in operation. From one of the quarries that became landfills and then urban parks, biogas is extracted that allows the production of electricity.

Secondary sector

Montreal is an important port city, at the mouth of the St. Lawrence Seaway that connects it to the industrial centers of the Great Lakes. As the largest port in eastern Canada, it is a transshipment point for grain, petroleum products, machinery and manufactured goods. The country's first port in terms of container traffic, traffic totaled nearly 26 million metric tons of goods. For this reason, the city is part of the main axis of the Canadian railways and remains a major railway city.

The petrochemical industry, very present in the east of the island, was the province's largest refinery until the closure of the Shell refinery in 2010. Since then, the Suncor and Gulf Oil refineries have maintained a combined capacity of 225,000 barrels per day. Oil and distillates are transported by four pipelines, trains, boats and trucks. Fuels are not the only production, however, and the plants in Parachem, Indorama PTA and Selenis, for example, form a complete polyester synthesis chain.

The aeronautics industry employs approximately 40,000 people in the Montreal area. This industry, which includes masters, of which Bombardier Aerospace and Bell Helicopter are the most important, equipment manufacturers (Honeywell, Lokheed Martin, Thales) and subcontractors, produces the main Montreal export.

Tertiary sector

Montreal has a stock market with the Montréal Stock Exchange. Since , the company has been united with the Chicago Climate Exchange to create the Montreal climate market, a market for environmental products.

The video industry has exploded since 1997 and the opening of Ubisoft Montreal. More recently[When?], the city has attracted world-renowned studios such as Electronic Arts, Eidos Interactive, BioWare, THQ and Gameloft. Thanks to a specialized local workforce and business tax credits, Montreal has become one of the five global centers for interactive digital media development with 85 companies and 5,300 jobs.

In 2012, Montreal's metropolitan area welcomed nearly 8 million tourists, up 6.5% since 2008. Traveler's Digest and askmen.com ranked Montreal among the "29 cities to visit" in the world.

Organizations